FOR STUDENTS

Chapters

Chapter 1: Contexts for Reading the Gospels

Chapter Summary

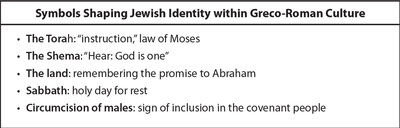

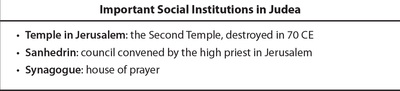

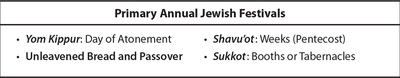

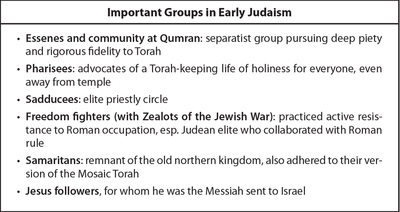

It is important to consider the setting in which the Gospels occur, a setting dominated by the Roman Empire, as we shape our responses to these stories. Jesus was a Jew, and Jews comprised about 5 to 10 percent of the Roman Empire. While many were confused by Jewish monotheism and customs, many characteristics of the Jewish religion—like its antiquity, strict moral code, and strong sense of community—drew some Gentiles to convert. Jews worshiped together in meeting places or gatherings called the synagogue and had many identity-shaping symbols. They also participated in several annual festivals, centered at the Second Temple at Jerusalem. The Sanhedrin was the highest council of the Jews at Jerusalem that exercised oversight of judicial and financial concerns of the city. There was considerable diversity of views within Judaism itself, with many distinct Jewish groups or social movements, such as the Pharisees, Essenes, Sadducees, Samaritans, freedom fighters, and, of course, Jesus’ followers.

The Torah, which comprises the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, tells the story of God’s election of Israel to be a covenant people. They felt connected to the land that God had promised to Abraham and his descendants. Jews needed to come to terms with the dissonance between their sacred texts, which promised them land and royalty, and living daily under domination of the Roman Empire, especially since the majority of the population lived at or below subsistence level and life expectancy was short.

The Torah, which comprises the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, tells the story of God’s election of Israel to be a covenant people. They felt connected to the land that God had promised to Abraham and his descendants. Jews needed to come to terms with the dissonance between their sacred texts, which promised them land and royalty, and living daily under domination of the Roman Empire, especially since the majority of the population lived at or below subsistence level and life expectancy was short.

Key Points

Context Matters: The Gospels in the Setting of First-Century Judaism

Jews within Greco-Roman Culture

Context Matters: The Gospels within the Early Roman Empire

- The situation of the readers then, and of readers today, is important for shaping our responses to the Gospel stories

- Jesus was a Jew, born and raised in Palestine, and all of his earliest followers were Jewish

Jews within Greco-Roman Culture

- The Torah, which comprises the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, tells the story of God’s election of Israel to be a covenant people

- The Jewish belief in one God (monotheism) is expressed in the Shema (Deut. 6:4-9)

- The Jewish people felt a special connection to the land of Palestine

- Jews observed a day of rest, called the Sabbath, from sunset on Friday until sunset on Saturday

- Circumcision was a traditional Jewish custom for males that served as an identity marker

- The Second Temple at Jerusalem was an important social and economic institution, but was destroyed in 70 CE during the Jewish war against Rome. It was built after the first temple had been destroyed by the Babylonians around 587 BCE.

- Jewish festivals centered at the temple were Passover, Sukkot (Booths or Tabernacles), Shavu’ot (Weeks or Pentecost), and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement)

- The Sanhedrin was the highest council of the Jews at Jerusalem, and exercised oversight of judicial and financial concerns of Jerusalem. It was presided over by a high priest and included elite priests and lay scribes.

- The synagogue was a gathering place also known as a Jewish house of prayer (and worship)

- Some of the Jewish groups or social movements were the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, Zealots, Samaritans, and the followers of Jesus

Context Matters: The Gospels within the Early Roman Empire

- The Roman Empire was a geographically expansive and ethnically diverse society with a primarily agrarian economy

- Power, wealth, and public leadership was concentrated in the hands of a very limited number of elite, no more than 3 percent of the population

- The Emperor held an enormous amount of power and was acclaimed as a savior and a “son of god”

- In the world of Jesus and the Gospels, politics, economics, and religion were all bound up together

- The freedom fighters (Zealots) launched a revolt against Rome, which led to defeat of the Jewish forces and the destruction of the temple in 70 CE

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- What are the primary symbols that shape Jewish identity in the first century? How did these symbols set the Jewish community apart from others in the Greco-Roman culture?

- What were three major social institutions in Judea? How did they maintain Jewish life?

- Describe the four distinct social movements of the Essenes, Pharisees, Sadducees, and the Zealots.

- How would you describe life in Palestine within the Roman Empire? How did the Roman Empire influence the lives of Jews in Palestine? What were the people’s various responses to the Empire?

Chapter 2: Jesus and the Emergence of the Gospels

Chapter Summary

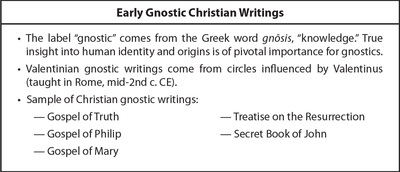

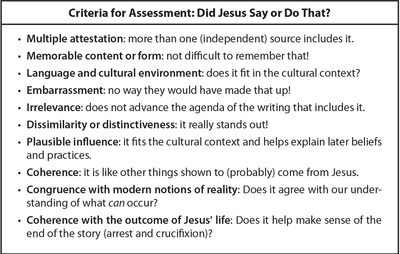

Jesus was remembered by early Christians in diverse ways. The “problem of the historical Jesus” is how we determine who Jesus really was given the multiple perspectives in our sources for his life and work. There are several criteria we can use to help us in our quest. These criteria include determining whether a particular event or saying was confirmed by multiple sources: whether it fits the cultural context, whether it is distinctive, and more. Based on these criteria, we can come up with a plausible general sketch of Jesus’ public career.

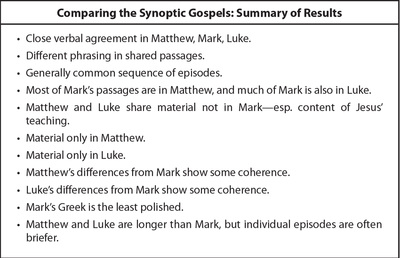

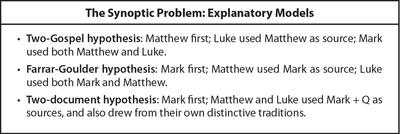

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are often viewed together as the Synoptic Gospels because they have many commonalities. However, close analysis reveals notable differences in wording, sequence, and inclusion or exclusion of certain events. Most scholars agree that at least one of the Gospels has been used as a written source by the authors of the other Gospels. Three models exist to try to explain how the Synoptic Gospels are related to each other (referred to as “the Synoptic Problem”): the two-Gospel hypothesis, Farrar-Goulder hypothesis, and the two-document hypothesis.

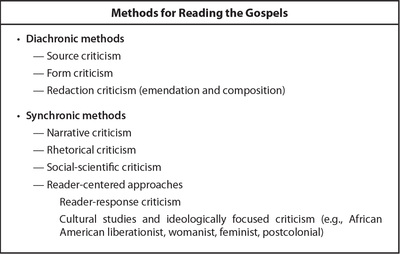

Because ancient manuscripts have been translated and reproduced thousands of times throughout the centuries, they contain many variations in wording. The discipline of text criticism attempts to provide as reliable a text as possible that can be used for interpretation. Once we have a reliable text, there are a variety of diachronic and synchronic methods used for interpreting the Gospels.

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are often viewed together as the Synoptic Gospels because they have many commonalities. However, close analysis reveals notable differences in wording, sequence, and inclusion or exclusion of certain events. Most scholars agree that at least one of the Gospels has been used as a written source by the authors of the other Gospels. Three models exist to try to explain how the Synoptic Gospels are related to each other (referred to as “the Synoptic Problem”): the two-Gospel hypothesis, Farrar-Goulder hypothesis, and the two-document hypothesis.

Because ancient manuscripts have been translated and reproduced thousands of times throughout the centuries, they contain many variations in wording. The discipline of text criticism attempts to provide as reliable a text as possible that can be used for interpretation. Once we have a reliable text, there are a variety of diachronic and synchronic methods used for interpreting the Gospels.

Key Points

From the Gospels to Jesus: The Problem and Quest of the Historical Jesus

The Genre of the Gospels

The Formation of the Gospels

Reading the Gospels

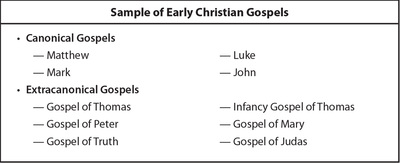

- The four canonical Gospels are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John

- Documents that were not included in the accepted canon include The Gospels of Thomas, Peter, Truth, Mary, Judas, and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas

- Multiple pictures of Jesus emerge throughout the Gospels because they were written many years after Jesus died and with a particular audience, setting, and set of convictions

- There are multiple criteria we can use to help determine the plausibility of certain events in the Gospels

- Jesus often used brief stories called parables to convey his vision of God

The Genre of the Gospels

- The word “gospel”--euangelion in Greek—means “good news”

- The Gospels are often categorized as bioi, or “biographies,” though they employ biographical conventions flexibly

- Many scholars classify Luke and Acts together as a history

- Because it does not conform to any prior literary genre, some scholars place the Gospel of Mark in a new genre, which they call the (Christian) Gospel

The Formation of the Gospels

- Matthew, Mark, and Luke are conventionally classified as the Synoptic Gospels because of their similarities, though comparative study reveals many important differences

- There are many examples of events that are common to all three of the Synoptic Gospels. One is Jesus’ forty days of testing by the devil in the wilderness (Matt. 4:1–11; Mark 1:12–13; Luke 4:1–13). While the event occurs in all three Gospels, language, sequence, and important details vary among them.

- John presents a generally independent account of Jesus’ ministry but does include a few of the same episodes

- The Synoptic Problem is the attempt to explain the inter-relationships between the Synoptic Gospels

- The two-Gospel hypothesis posits that Matthew was written first, then Luke employed Matthew as a source, and Mark used both Matthew and Luke

- The Farrar-Goulder hypothesis posits that Mark came first, Matthew used Mark as a source, and Luke used both Mark and Matthew

- The two-document hypothesis proposes that Mark came first and Matthew and Luke used both Mark and another common source, Q, while also drawing from their own distinctive traditions

Reading the Gospels

- Because ancient manuscripts have been reproduced and translated over many years, text criticism is a method that attempts to determine a reliable text that approximates the wording of the original manuscript

- Diachronic methods for interpreting the Gospels approach the meaning of the text by probing its history. Diachronic methods include source criticism, form criticism, and redaction criticism.

- Synchronic methods of interpretation work with the text in its final form. These methods include narrative criticism, rhetorical criticism, social-scientific criticism, and reader-centered approaches like reader-response criticism and ideologically-focused criticism.

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- What is the “problem of the historical Jesus”? What are several factors that make it difficult to construct an exact depiction or portrait of Jesus? What are some criteria used to determine reliability of historical elements?

- Provide an example of an event that occurs in multiple Gospels. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

- What is “Q” and how is it incorporated into the two-document hypothesis?

- What are the differences between diachronic and synchronic approaches to reading the Gospels? List a few examples of each.

- With various methods for reading the Gospels, how are readers able to achieve helpful interpretations of the texts that do not simply make it say what one wants it to believe?

Chapter 3: The Gospel according to Mark

Chapter Summary

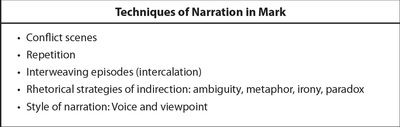

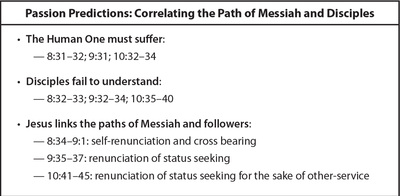

Mark was likely written during or just after a time of Jewish rebellion in Judea against the Roman Empire, and it conveys a powerful counter-imperial message. Mark employs several techniques of narration, including repetition, conflict scenes, intercalation, and irony. The narrator often speaks in the present tense, even while describing historical events, and the narrator’s point of view is generally regarded as being closely aligned with God and the character of Jesus. The Gospel of Mark situates the mission of Jesus within the larger story of Israel, with frequent references to Israel’s Scriptures. Jesus often argues with other Jewish teachers, such as the Pharisees, about scriptural interpretation. His teaching authority is a central feature of Mark’s characterization of him and highlights the motif of hope in the midst of suffering.

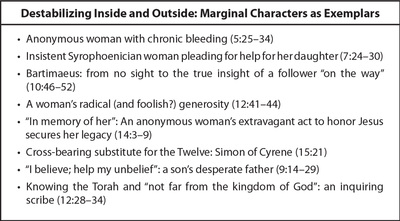

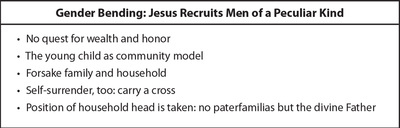

The identity of Jesus is often presented as a secret or mystery. His disciples are repeatedly unable to comprehend his teaching and significance, and their status as privileged insiders becomes destabilized by characters on the outside of society who sometimes better embody the character of discipleship. Although Jesus expresses a preference for Jewish people, his encounters with Gentiles point the way to a broader inclusion of people within the community of Jesus-followers. Rebuffing traditional Greco-Roman understandings of gender roles, Jesus’ male followers are challenged to embrace nonconventional roles of masculinity in order to follow Jesus. The role of women is ambiguous: whereas women are often shown to be assertive initiators of action, these women also typically remain nameless.

The identity of Jesus is often presented as a secret or mystery. His disciples are repeatedly unable to comprehend his teaching and significance, and their status as privileged insiders becomes destabilized by characters on the outside of society who sometimes better embody the character of discipleship. Although Jesus expresses a preference for Jewish people, his encounters with Gentiles point the way to a broader inclusion of people within the community of Jesus-followers. Rebuffing traditional Greco-Roman understandings of gender roles, Jesus’ male followers are challenged to embrace nonconventional roles of masculinity in order to follow Jesus. The role of women is ambiguous: whereas women are often shown to be assertive initiators of action, these women also typically remain nameless.

Key Points

Historical Questions: Who, When, Where, and What?

Literary Design and Techniques of Narration

Central Motifs and Concerns

Ending the Story: The Rhetorical Impact of an Open-Ended Narrative

- The Gospel’s authorship cannot be determined today, though traditionally it was attributed to Mark, who is mentioned also in the New Testament epistles

- This Gospel was likely written shortly before or after the destruction of the temple (70 CE) in Rome or more likely in some other location outside of, but in proximity to, Palestine

- Mark’s narrative is shaped by and speaks to a world dominated by the Roman Empire. It bears specific markers of hostility, potential persecution for disciples, and other issues associated with imperial domination.

- Mark bears some features of many literary genres including biographies, tragic drama, and popular novels, and it deploys these in sometimes surprising ways

Literary Design and Techniques of Narration

- Geography, particularly spatial movement from Galilee to Jerusalem, is crucial to the plot in Mark, which emphasizes the motif of “the Way”

- Repeated scenes of conflict between Jesus and his disciples regarding Jesus’ passion predictions (three times within 8:22-10:52) help the reader better understand Jesus’ identity and vocation, and understand the implications for the disciples’ vocation

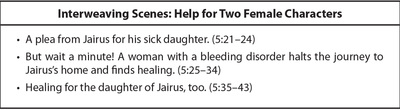

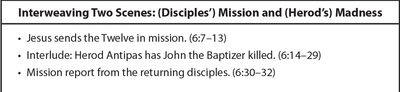

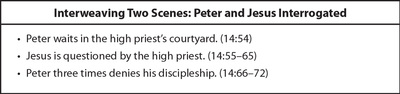

- Intercalation is a distinctive Markan narrative technique, which helps the reader reflect on ways in which two interlocking vignettes are mutually instructive

- Mark employs several rhetorical strategies of indirect communication—especially irony—that requires active engagement from the reader to discern meaning

- Mark’s narrator often uses present tense verbs to describe historical events, and includes Aramaic phrases that are then translated; these literary techniques lend immediacy to readers' experience of the story

- The pacing in Mark is swift and conveys urgency until Jesus reaches Jerusalem, when it slows down and thus conveys the gravity of events

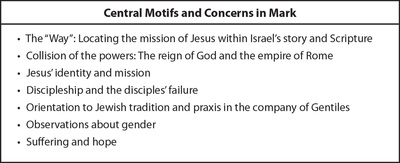

Central Motifs and Concerns

- Mark situates the mission of Jesus (the “Way”) within the story of Israel and connects it with the Jewish Scriptures

- Mark often depicts the collision of powers between the reign of God and the Roman Empire and delivers a powerful counter-imperial message, often through ironic parody

- Jesus’ identity as Messiah is often presented as a secret or mystery

- Jesus’ disciples are frequently unable to comprehend Jesus’ teaching and significance, whereas marginal characters sometimes exemplify true discipleship

- Jesus often engages in animated debates with other Jewish teachers about wise interpretation and faithful practice of the Torah

- Jesus’ encounters with Gentiles anticipate eventual inclusion of Gentiles within the community of Jesus-followers

- Men carry most of the action in Mark, though Jesus asks his male followers to adhere to nonconventional notions of masculinity in the Greco-Roman world, e.g., eschew both wealth and honor seeking, affirm the young child as community model, forsake family and household, and bear a cross.

- Despite mostly being nameless, women in Mark’s story are often shown to be assertive initiators of action. They also have intriguing and ambiguous roles.

- Jesus’ teaching authority is a central feature of Mark’s characterization of him, and highlights the motif of hope in the midst of suffering

Ending the Story: The Rhetorical Impact of an Open-Ended Narrative

- Recent scholarship regards 16:1-8 as the original ending of the Gospel, and the longer ending as the result of early Christians’ attempts to alleviate their dissatisfaction with it

- The open-ended ending suggests that assurance for the future rests in the reliability of Jesus’ promise

- Mark’s audience is tasked with seeking deeper understanding that will direct and energize their ongoing response to the narrative, using Jesus as a model for enacting the good news of God’s reign in their own lives

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- What are the major techniques of narration in Mark? Note an example of each.

- What are some common features and also some differences in the story details of Jesus’ three passion predictions? What do these passages convey about Jesus’ identity, vocation, and about the vocation of the disciples?

- Provide three examples of Jesus’ mission as a continuation of Israel’s story and Scripture.

- How does the reign of God as inaugurated by Jesus’ ministry call people to change their life? What claims and commitments should followers should turn away from (i.e., repent)?

- Describe the counter-imperial character of the reign of God as inaugurated in Jesus’ ministry.

- Describe the various types of silence-secrecy featured in Mark, including the messianic secret.

Chapter 4: The Gospel according to Matthew

Chapter Summary

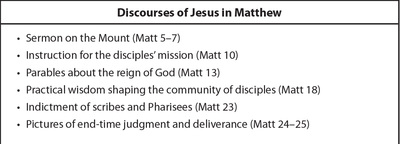

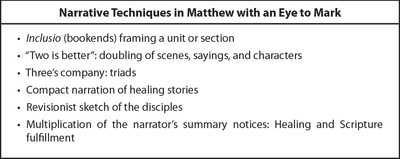

Matthew draws from and expands on Mark’s narrative. It makes a concerted effort to legitimize the claim of Jesus as Messiah, immediately recounting Jesus' ancestry in a manner that inserts him into the ongoing history of Israel. Matthew presents Jesus’ public career in five segments, alternating between extensive discourses of Jesus and accounts of his activity. The technique of inclusio provides a structuring framework and effectively reinforces the central concerns and affirmations of that section of the narrative. Other narrative techniques include patterns of two and three, compact narration of healing stories, a more favorable presentation of the disciples compared to Mark, and a frequent emphasis on the effective healing ministry of Jesus.

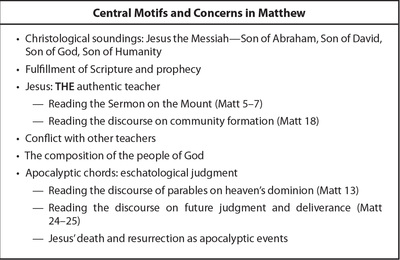

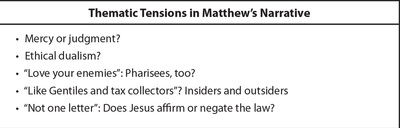

Several motifs emerge in Matthew, including a strong Christological focus, a concern with the fulfillment of Jewish Scripture and prophecy, and an emphasis on eschatological judgment. Matthew also presents Jesus as the definitive teacher—often in conflict with other teachers—as illustrated in the Sermon on the Mount and the discourse on community formation. Several conflicting notions arise throughout in relation to mercy/judgment, ethical dualism, the appeal for love of enemies, relationships with insiders/outsiders, and adherence to the Torah.

Matthew has played an important role in shaping the faith and practice of Christianity, but has often been toxic in relation to the Jewish religion and people.

Several motifs emerge in Matthew, including a strong Christological focus, a concern with the fulfillment of Jewish Scripture and prophecy, and an emphasis on eschatological judgment. Matthew also presents Jesus as the definitive teacher—often in conflict with other teachers—as illustrated in the Sermon on the Mount and the discourse on community formation. Several conflicting notions arise throughout in relation to mercy/judgment, ethical dualism, the appeal for love of enemies, relationships with insiders/outsiders, and adherence to the Torah.

Matthew has played an important role in shaping the faith and practice of Christianity, but has often been toxic in relation to the Jewish religion and people.

Key Points

Historical Questions: Who, When, Where, and What?

Literary Design

Other Narrative Strategies (with an Eye to Mark)

Central Motifs and Concerns

Is Matthew a Coherent Narrative? Exploring Thematic Tensions

- The author is unknown, though there are similarities between the scribe described at the close of the parables discourse (ch. 13) and the author, suggesting it could be at least a general self-portrait

- Most agree that Matthew was first composed in Greek

- Matthew’s narrative makes a concerted effort to legitimize the claim of Jesus as Messiah who has come to restore Israel

- Antioch is often suggested as the initial setting of Matthew

- Matthew was likely written around 80-90 CE

- Matthew’s narrative fits closely with the Greco-Roman biography tradition with its attention to family origins, remarkable birth story, and childhood narrative

- Matthew uses the biographical narrative not simply to extol Jesus as its central figure, but also to commend his manner of life as a model for readers and to undergird the claim of Jesus’ Jewish heritage

Literary Design

- With an opening genealogy, Matthew inserts the life of Jesus into the ongoing history of Israel—indeed, as its fulfillment or culmination

- Matthew joins and expands on Mark’s narrative and presents Jesus’ teaching in several major discourses, including the Sermon on the Mount, instructions for mission, the parables discourse, the discourse on the community of disciples, and an eschatological discourse about the perils and promise of the future

- Matthew's literary structure is less geographically oriented than Mark

Other Narrative Strategies (with an Eye to Mark)

- Matthew frames portions of the narrative through inclusio (“bookends”)

- Matthew often presents doubling of scenes, sayings, and characters

- Patterns of three (triads) are also used

- The presentation of individual healing stories, compared to Mark, is compact and stereotypical

- Matthew offers a much more favorable presentation of the disciples than Mark

- Matthew frequently draws readers' attention to the healing ministry of Jesus

Central Motifs and Concerns

- A key characteristic of Matthew is its interest in the identity and significance of Jesus as the Messiah (Christology)

- Matthew also emphasizes prophecy and fulfillment of the Jewish Scriptures through Jesus

- The Sermon on the Mount is Jesus’ inaugural teaching to newly recruited disciples (and to the crowd listening in, too) that explains what life governed by the claims and commitments of God’s reign looks like

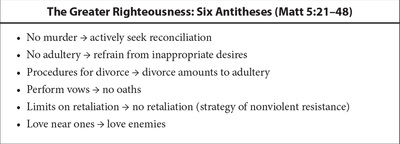

- With his six antithesis in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus asserts that his teaching upholds, and is even more stringent than, what listeners have been taught about the Torah and Prophets

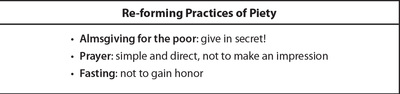

- The Sermon on the Mount also sketches ritual practices that express authentic piety: almsgiving, prayer, and fasting

- The discourse on community formation asks disciples to prize humility over high status and public reputation, explores what happens when someone strays from the community, and emphasizes forgiveness

- Matthew presents conflict between Jesus and other teachers to a more dramatic degree than Mark, with the identity of the Messiah and composition of God’s people both at stake

- Jesus criticizes those who fail to perceive that the Messiah is among them

- In Mark, the parables are intended to provoke misperceptions, whereas in Matthew, the people are choosing not to perceive—it is the people, not the message

- The Gentiles are often represented in ambiguous ways, suggesting that the composition of God’s people is undergoing redefinition, and often determined by conduct

- The parable of the sheep and the goats sketches a picture of universal judgment that is ambiguous (whom do the sheep and the goats represent?), requiring readers to make a choice about how they will interpret it

Is Matthew a Coherent Narrative? Exploring Thematic Tensions

- Matthew highlights the importance of mercy, while also emphasizing the severity of judgment

- Jesus emphasizes that the world comprises good and bad, while at the same time commending love of enemies

- Jesus engages in heated debates with Pharisees, but also tells disciples to love enemies

- Perspectives on insiders and outsiders (e.g., tax collectors, Gentiles) are inconsistent, poking at the rigid boundaries between those in the community and those outside

- Jesus is presented as an exponent of the Torah while also offering teaching that is against or critical of Scripture, as it is commonly interpreted

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- How does Matthew connect the story of Jesus with the history of Israel?

- What are the five major discourses of Jesus’ teaching and what are the main themes emphasized in each?

- List and describe at least three central features of Matthew that identify Jesus as the Messiah (Christology).

- What kind of life does the Sermon on the Mount commend? Is it realistic and attainable?

- What is the core message in Matthew about eschatological judgment and hope for the future?

- Identify at least three thematic tensions in Matthew’s narrative. Explain each using your own words.

- Which two verses form the inclusio (bookend) for the Gospel of Matthew as a whole? What theme do these verses emphasize regarding the significance of Jesus in Matthew?

Chapter 5: The Gospel according to Luke

Chapter Summary

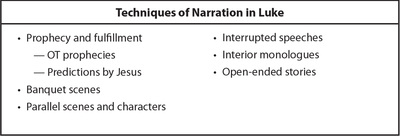

Like Matthew, the Gospel of Luke builds on and expands the material in Mark. It also shares much of the material in Matthew that does not appear in Mark; in several places reorders the sequence of events in Mark; and includes material found only in Luke. Luke may be read as an apologetic history that shapes the identity of the early Christians and connects their story to the history of the Jewish people. Techniques of narration used in Luke include prophecy and fulfillment, repeated banquet scenes, parallel scenes and characters, interrupted speeches, interior monologues by characters, and open-ended stories that leave decision and response to the listener/reader.

Luke’s narrative features several role reversals that turn upside-down and inside-out social convention and patterns of governance and control. Those of lower status, such as the poor, are elevated, and those on the outside of society, such as sinners, are brought in. Empire is portrayed ambiguously, inviting readers to a countercultural understanding of power and status, but not necessarily encouraging open rebellion. Ultimately, Luke offers an expansive vision of a multiethnic, multicultural people of God that will share resources, honor the least, restore the lost, and love the outsider, even the enemy. Its closing chapter anticipates the mission of Jesus’ followers in its sequel, Acts.

Luke’s narrative features several role reversals that turn upside-down and inside-out social convention and patterns of governance and control. Those of lower status, such as the poor, are elevated, and those on the outside of society, such as sinners, are brought in. Empire is portrayed ambiguously, inviting readers to a countercultural understanding of power and status, but not necessarily encouraging open rebellion. Ultimately, Luke offers an expansive vision of a multiethnic, multicultural people of God that will share resources, honor the least, restore the lost, and love the outsider, even the enemy. Its closing chapter anticipates the mission of Jesus’ followers in its sequel, Acts.

Key Points

Historical Questions: Who, When, Where, and What?

Literary Design and Techniques of Narration

Central Motifs and Concerns

- Luke does not identify its author by name; some second-century traditions suggest that he was a physician, but this cannot be reliably established

- Luke’s attention to the Jewish Scriptures suggests that he might have been a Jew or more likely a Gentile who was a “God-fearer” familiar with the Jewish community and its traditions

- Luke’s narrative addresses concerns of the early Christians about their identity and place in both society and Israel’s story as a whole

- Likely written late in the first or early in the second century in an urban center in the eastern Mediterranean and set within the Roman Empire

- May be read as a biography, but in tandem with Acts better fits the genre of history, specifically an apologetic history

Literary Design and Techniques of Narration

- Like Matthew, Luke expands the Mark narrative and reinforces Jesus’ identity as Son of God

- The closing chapter of Luke anticipates the mission of Jesus’ followers in its sequel, Acts

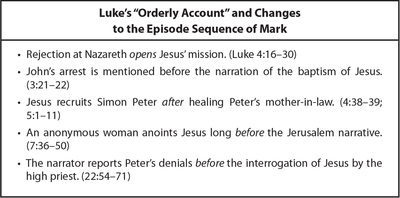

- Luke changes the sequence of several events from Mark (e.g., Jesus’ rejection at Nazareth in Luke 4:16-30 opens Jesus' mission, rather than occurring in the middle of it)

- Luke emphasizes journeys and configures space and time in meaningful ways

- The narrative device of prophecy and fulfillment reinforces the reader’s sense of the reliability of the account, confirms Jesus’ status as prophet-Messiah, and roots the story of Jesus in the story of Israel

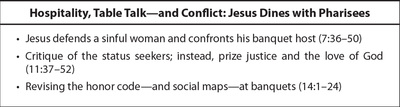

- Banquet scenes are a prominent feature of Luke's narrative and both express and challenge basic social values and practices (e.g., meals at the homes of Pharisees)

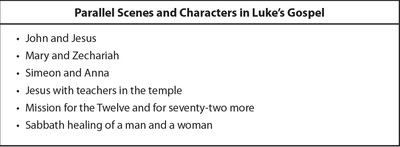

- Parallel scenes, characters, and occurrences are used to lend cohesiveness and continuity to the story and reinforce the audience’s impression that a (divine) purpose drives it (e.g., John and Jesus)

- Interrupted speeches are a prominent technique of narration in Luke and draw attention to both the content of the speaker’s message and the character of the audience’s response (e.g., Jesus’ speech to residents of Nazareth in 4:16-30)

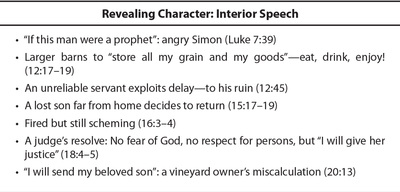

- Luke presents interior monologues that reveal the thoughts and attitudes of the character, often related to a choice that needs to be made—the question is thereby posed to the reader

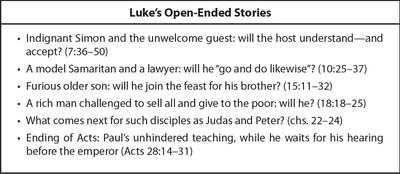

- Open-ended stories reroute a character’s decision to the Lukan audience: e.g., the reader isn’t told whether the lawyer follows the model of the Good Samaritan described in Jesus’ parable in Luke (10:25-37), or whether the older brother relents and joins the feast for his younger brother (15:11-32), or how the rich man finally responds to Jesus' call to him to renounce his wealth (18:18-25)

Central Motifs and Concerns

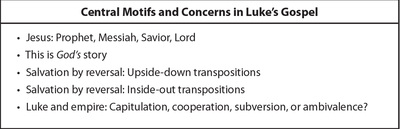

- Jesus is portrayed in Luke as prophet, Messiah, Savior, and Lord—the primary agent through whom God’s reign is enacted

- Jesus’ story is part of a larger narrative: the story of God with God's people Israel and ultimately, through Israel, all nations; God’s purpose drives Luke’s story

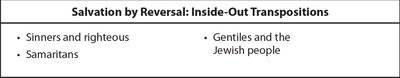

- Luke’s narrative features several role reversals that turn upside-down and inside-out social convention and patterns of governance and control

- Vertical (upside-down) reversals center on elevating those of lower-status, including the poor, women, and children

- Luke advocates for responsible use of wealth that includes sharing resources with those less fortunate

- Luke presents a “double message” about women that seems to affirm them as disciples yet often restricts them to conventional roles

- Jesus elevates children, who posses low status in Luke’s world, as model members of the reign or household of God

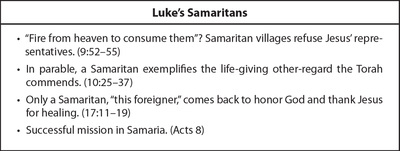

- Horizontal (inside-out) reversals focus on Jesus’ relationships with those on the margins of society, such as sinners and Samaritans

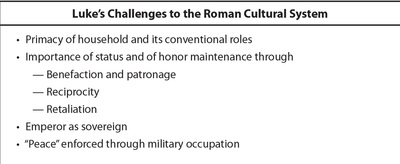

- Luke’s Gospel presents ambiguous images of empire, sometimes portraying agents of Roman rule favorably and sometimes not (the critique is often implicit)

- Luke does not push contemporary readers toward open rebellion against the empire, but invites them to a distinctive way of life in which God’s reign can be embodied in practice—within a community whose practices run counter to Roman rule and culture

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

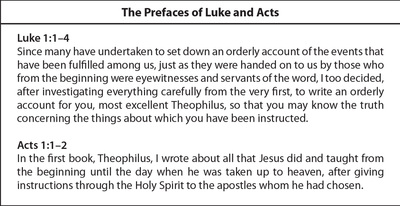

- Who is Theophilus? How could first readers of Luke relate to Theophilus as members of Jesus’ new movement?

- List at least three examples of prophecy and fulfillment in Luke. How does the author use prophecy and fulfillment as a literary device? What does the narrative device reinforce in readers' impression of the Gospel?

- How does Luke describe Jesus as prophet, Messiah, and the Human One (Christology)?

- What are upside-down and inside-out transpositions? How are they connected to God’s salvation in Luke's presentation of the message and actions of Jesus?

- What is Luke’s perspective regarding wealth and poverty? What would be the significance of this view for Luke’s audience?

- What is Luke’s “double message” about women? Give three examples of Luke’s treatment of women that show ambiguity toward their status and roles (i.e., both affirmation and restriction).

- Give examples from Luke's Gospel that show challenges to the Roman cultural system. How does the narrative adopt language of the Roman Empire yet also create space for living in God’s reign in a manner that runs counter to the empire?

Chapter 6: The Gospel according to John

Chapter Summary

While there are some features that John shares with the other Gospels, there are also significant differences. This is evident in the figuring of space and time, language and thematic focus, and the presentation of Jesus’ ministry. Moreover, although conflict appears in all the Gospels, John intensifies it, and focuses it sharply on Christological claims, which sets it apart from the other Gospels. The frequent presentation of debates and dualistic language makes the Gospel's account of Jesus' ministry almost like a sustained trial.

The techniques of narration used in John’s Gospel create a community of understanding between narrator and reader that is not shared by the characters in the story, and leads the reader toward embracing the author’s perspective. These narrative techniques include riddles and misunderstanding, explanatory comments by the narrator, irony, metaphor, and duality. Signs and discourses reveal both the identity of Jesus and the character of his mission as well as the beliefs of those who come into contact with him.

John presents Jesus as the revealer of God, and belief in him (acceptance of his revelation) leads to eternal life. Despite this, Jesus collides with the world as it largely opposes and rejects his mission, and he prepares his followers for similar opposition. However, through the Spirit (Paraclete), the disciples will find guidance and encouragement as they continue to carry out Jesus’ work after his departure.

The techniques of narration used in John’s Gospel create a community of understanding between narrator and reader that is not shared by the characters in the story, and leads the reader toward embracing the author’s perspective. These narrative techniques include riddles and misunderstanding, explanatory comments by the narrator, irony, metaphor, and duality. Signs and discourses reveal both the identity of Jesus and the character of his mission as well as the beliefs of those who come into contact with him.

John presents Jesus as the revealer of God, and belief in him (acceptance of his revelation) leads to eternal life. Despite this, Jesus collides with the world as it largely opposes and rejects his mission, and he prepares his followers for similar opposition. However, through the Spirit (Paraclete), the disciples will find guidance and encouragement as they continue to carry out Jesus’ work after his departure.

Key Points

Historical Questions: Who, When, Where, and What?

Literary Design

Techniques of Narration

Central Motifs and Concerns

- The identity of the writer of the Gospel is unknown, though it has often been credited to the apostle John; the narrative presents itself as based on the eyewitness testimony of an anonymous "beloved disciple"

- While it is common to consider John the latest of the four Gospels, it is conceivable that some version of it appeared before Luke

- Early Christian tradition places the composition of John at Ephesus, though a location closer to Palestine is perhaps more likely

- John employs the genre of biography in a way that emphasizes a trial motif

Literary Design

- The opening of John’s Gospel echoes the opening of Genesis, immediately presenting Jesus as the revealer of the Creator God

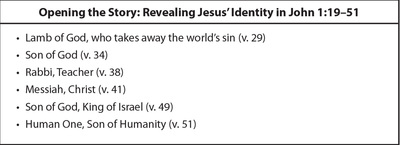

- Already in chapter 1, John gives Jesus several labels that reveal his identity: Lamb of God; Son of God; Rabbi/teacher; Messiah/Christ; Song of God, King of Israel; Human One/Son of Humanity

- Jesus makes repeated references to “the hour,” and eventually readers learn the “hour” is the crucifixion

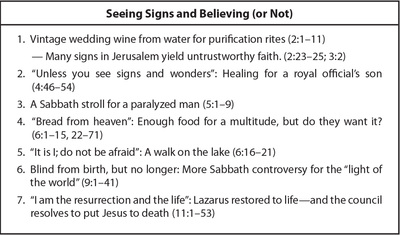

- There are numerous examples of Jesus revealing himself through extraordinary actions, which the narrator calls "signs," and which often incite debate from others

- While the prominent Pharisee Nicodemus misunderstands Jesus, the marginal Samaritan woman engages in serious theological dialogue with Jesus and not only comes to believe in him but also leads her whole village toward belief

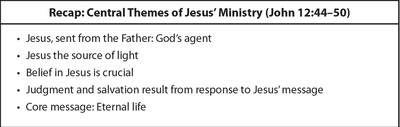

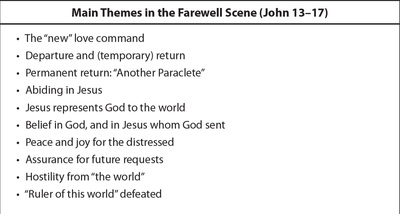

- A lengthy farewell scene (in chs. 13-17) features speech and dialogues in which Jesus emphasizes several key themes and often responds to the disciples’ confusion in a manner that instructs readers

- John’s passion account is dominated by a dramatically staged, seven-scene encounter between Jesus and Pontius Pilate

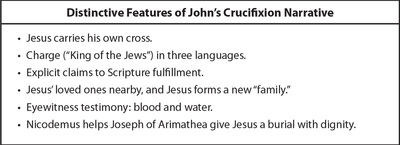

- There are several distinctive features of John’s crucifixion narrative: Jesus carries his own cross, the capital charge is written in three languages, there are explicit claims to Scripture fulfillment, Jesus’ loved ones are close by, there is eyewitness testimony that blood and water flowed from Jesus' side, and Nicodemus helps with the burial

- Thomas’s skepticism after the resurrection of Jesus highlights the question of whether faith without sight (and signs) is possible

- John closes with a final resurrection appearance by Jesus to a group of seven disciples that focuses on the roles of Simon Peter and the anonymous “Beloved Disciple”

Techniques of Narration

- Jesus regularly uses riddles that divide his audience into insiders who understand and outsiders who don’t, prompting readers to ponder their meaning

- Characters often misunderstand what Jesus says, prompting Jesus to explain his meaning more fully for the reader’s instruction

- The narrator repeatedly offers explanations to guide the reader

- Irony is a regular narrative technique, and is especially apparent in the scene depicting the raising of Lazarus from the dead, which sets in motion a series of events that lead to Jesus’ own death

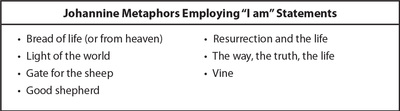

- Metaphorical images are used to support the claim that Jesus is the source of life (e.g., several “I am” statements by Jesus)

- Dualistic language throughout John emphasizes the tension between dominant society and the alternative world governed by God

- Jesus performs signs to disclose the truth about God, which often result in mixed responses from those who witness them, including hostile opposition

- Frequent debates reveal the identity of Jesus and character of his mission, and also reveal the stance of those in dialogue with him

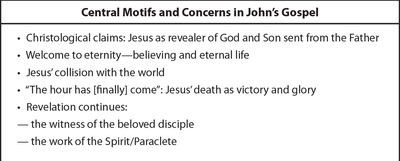

Central Motifs and Concerns

- John presents Jesus as the revealer of God, who does the work and speaks the word of God

- The dominant image in John is eternal life that persists beyond physical death for all those who believe

- Jesus collides with the world as it opposes and rejects his mission

- When the time comes for Jesus’ crucifixion (“the hour”), the purpose of his coming to the world is finally accomplished despite its being through torture and humiliation

- The anonymous “beloved disciple” is portrayed as a model/representative follower of and witness to Jesus

- The Spirit (Paraclete) guides and encourages the community of disciples as they continue to carry out the work of Jesus after his departure

Flash Cards

Begin studying by choosing a study mode in the lower right-hand corner. By clicking on options in the upper right-hand corner, you can choose to begin with terms or definitions, among other study options.

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- What are the significant differences between John and the Synoptic Gospels? What are some similarities between John and the other Gospels?

- How does the Gospel of John describe Jesus’ identity in the narrative opening (Christology)? How does John connect Jesus with the creation story at the opening of Genesis?

- What are the seven signs in John's Gospel that point to Jesus’ significance? What do they reveal about him?

- What is the Paraclete? Why does Jesus leave the Paraclete with the disciples?

- Describe the central themes in Jesus’ prayer in John 17. What is the significance of this prayer for the disciples, and for readers?

- Who are Nicodemus, the Samaritan woman, Thomas, and the beloved disciple? How does John reveal Jesus’ mission through each of their stories?

- What are “I am” statements? What do they reinforce about Jesus’ identity?

- How does John develop the theme of "eternal life"? In the teaching of Jesus about eternal life, what is the relationship betweeen the present and the future? How does John place the accent differently than the other (Synoptic) Gospels do?

Chapter 7: From Ancient Gospels to the Twenty-First Century

Chapter Summary

What is the significance of the Gospels in the midst of today’s world, one flooded with headlines showcasing injustice and violence? The Gospels offer many interpretive challenges for readers today, particularly in their portrayals of judgment, anti-Judaism, gender roles and marriage, empire, other-regard, and wealth. It is crucial to gain clarity about the cultural and social influences that shaped the Gospels in the time they were written. In the Gospels, Jesus emphasizes love and compassion toward all, including the poor and marginalized.

Key Points

Probing for Connections, Listening for Harmonies

From First to Twenty-First Century: Interpretive Challenges and Ethical Resources

- The four Gospels present four distinctive portraits of Jesus, but also hold common concerns and commitments

- In each Gospel, Jesus embraces persons on the margins of society and showcases the mercy and forgiveness of God

- All the Gospels offer hope in the midst of the adversity and danger going on in the world around them

From First to Twenty-First Century: Interpretive Challenges and Ethical Resources

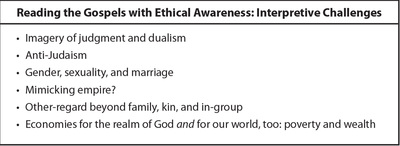

- In the Gospels, readers frequently encounter the theme of retributive or punitive judgment, but this often comes under severe critique that points the way to a pattern of nonviolent resistance and hospitality toward all others

- While the Gospels often present Jesus in conflict with the Jewish people, and thus potentially contribute to anti-Judaism, they also emphasize Jesus’ call to love all others

- While the Gospels generally assume the patriarchal social system of their world, Jesus offers a countercultural message that challenges conventional notions of the household and its priority, yet also holds the potential to revitalize household relationships

- Jesus presents a model of leadership that is in stark contrast to imperial Rome, a model that should be considered by readers today who live in powerful nations

- Jesus repeatedly urges acts of compassionate care toward those in need, including enemies and those outside one’s social or family circle

- Jesus emphasizes an ethic of generosity towards the poor and others vulnerable in society

Fast Facts

Study Questions

- What are some of the distinctive thematic emphases of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John?

- What are some of the commonalities among the four Gospels?

- Choose three of the themes you identified in questions 1 and 2 above. Discuss how they may apply to twenty-first-century readers.

- How do the Gospel accounts of conflict between Jesus and his Jewish contemporaries facilitate interpretations that may contribute to anti-Judaism? What are possible interpretations of these conflicts that do not promote anti-Judaism and are consistent with other central themes of the Gospels?

- Name three societal issues of the twenty-first century. How do the Gospels instruct or challenge readers to respond to those challenges in ways that reflect the mission of Jesus?